The Matrix features a memorable scene where Cypher, portrayed by Joe Pantoliano, engages with Neo, played by Keanu Reeves, in front of numerous monitors. While Neo perceives this as a stream of random green code, Cypher sees vibrant imagery: “I don’t even see the code,” he says. “All I see is blonde, brunette, redhead …”

Similarly, a cricket scorecard can appear incomprehensible to outsiders, filled with initials, abbreviations, and unfamiliar figures. However, to those knowledgeable in the game, these sheets of data illustrate the unfolding drama—dynamics of an innings, the pace of bowling, and nuances of partnerships.

According to BBC statistician Andy Zaltzman, “Scorecards are beautiful things. They’re like time machines. You can look at a scorecard from 1800 and, even with fairly minimal details, get a sense of how the game evolved. There’s a joy in the infinite variety of the possible narratives within a game.”

John Arlott, the esteemed commentator and poet, once called the scorecard “the most compressed and the most expansive form of literature.” A line like “Bradman b Hollies 0” serves as both a plot twist and a shocking conclusion. A string of low scores can evoke tension, while extras leading the charts, as seen with Bermuda’s women in 2008, becomes darkly humorous. For the discerning reader, scorecards narrate rich stories filled with characters, tension, and even humor.

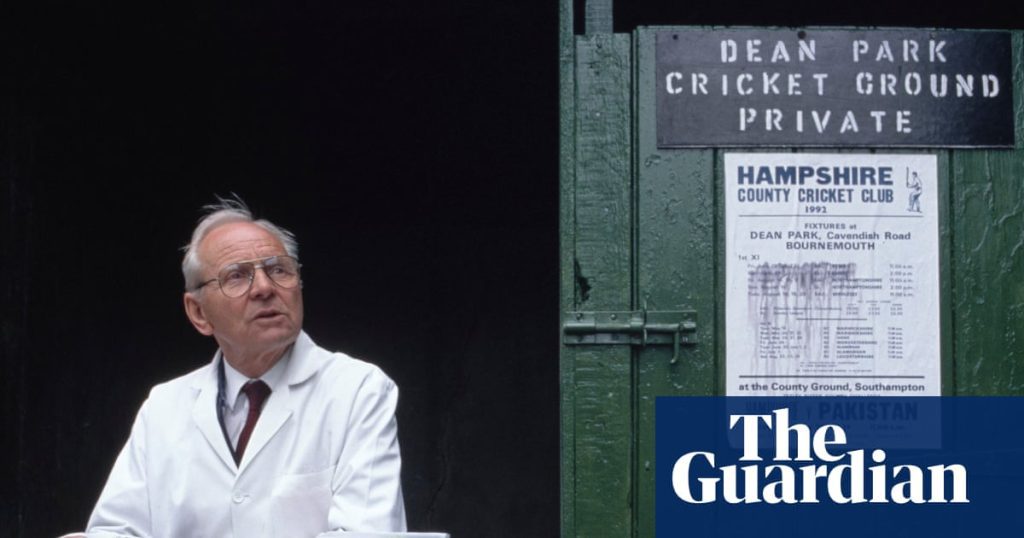

Bill Frindall, the BBC’s detailed scorer known as “Bearders,” described scorecards as “cricket’s autobiography, written one ball at a time.” For him, each entry in his meticulously recorded logs from 1966 to 2008 encapsulated the essence of each game.

The language of cricket scoring has been developed over time. Early scorecards were merely listings of runs, sometimes published weeks post-match. The oldest known scorecard dates to 1744 and details a game between London and Kent, marking only runs without the intricacies of dismissals or bowling figures.

As the game evolved, Samuel Britcher began producing more structured scorecards in the late 1700s. By the 1840s, scorecards included more detailed statistics, but the modern format— showing batters with their scores and dismissals alongside bowlers with their statistics—began taking shape in the early 20th century. These scorecards allow those not excelling on the field to participate, engaging fans who find joy in keeping track of the game. Modern scorers have made this process visually vibrant, utilizing colors to differentiate between players and their performances. However, Andrew Samson warns against losing traditional pen-and-paper methods in our increasingly digital world.

Zaltzman shares a handwritten score of the thrilling England vs. New Zealand World Cup final in 2019, capturing pivotal moments in colorful detail. He expresses his passion for creating scorecards, finding therapeutic pleasure in recording the events and completing a narrative of the match. “What could be better than that?” he muses.