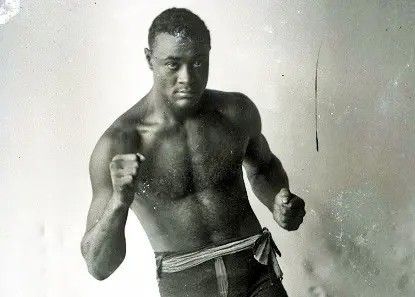

The Legacy of Harry Wills: A Fighter Defined by Missed Opportunities

Few exceptional boxers have been so unfairly characterized by the fights they couldn’t secure as “The Black Panther” Harry Wills. Following Wills’ death on December 21, 1958, many obituaries highlighted his near fight with Jack Dempsey, often overshadowing Wills himself.

Unlike many of his Black contemporaries who stayed active, engaged in fan-friendly bouts, or achieved international fame, Wills focused on earning money while consistently expressing his desire for a title shot. Like many Black heavyweights of his time, he encountered significant social and political barriers when seeking to fight white opponents.

In a tribute to Wills after his passing, Jersey Jones remarked, “White heavyweights were not too enthusiastic about facing the formidable Louisianan. Throughout his career, it’s likely he fought fewer than a dozen white boxers, dedicating himself primarily to engaging with leading Black fighters, except for Jack Johnson.” By the time Wills became a contender, Johnson’s era as a top fighter had nearly ended, and Sam Langford emerged as another noteworthy Black fighter without a world championship.

The historical record indicates that Wills and Langford fought around 17 times; however, Wills consistently claimed they faced each other 22 times. This necessity arose from Wills’ limited access to a diverse range of opponents. Despite this, he fought over 100 times while carefully managing his bouts to avoid debilitating losses and maintain hopes for a title shot, holding the Black heavyweight title for almost a decade.

Wills nearly secured a fight against Dempsey twice during his reign as Black heavyweight champion. In 1922, promoter Tex Rickard arranged a matchup, printed tickets, and scheduled it at the Boyle’s Thirty Acres venue, constructed for Dempsey’s previous defense. However, Dempsey’s conflict with Rickard led to the cancellation, leaving Wills with a significant payday for a fight that never happened.

Years later, when discussions resumed, the New York State Athletic Commission’s leader, William Muldoon, intervened. A strict former Greco-Roman wrestling champion, Muldoon feared that a mixed-race bout would incite riots—a concern stemming partly from the racial tensions following Jack Johnson’s victory over James Jeffries. Although not entirely unfounded, this apprehension was likely used to keep the heavyweight title within certain racial confines. Ultimately, it proved effective, as a Black heavyweight champion would not emerge again until Joe Louis a decade later.

Harry Wills was not only a talented fighter but also a personable young man from New Orleans who aspired to be a jockey before turning to boxing. Known for his kind nature and willingness to help, an anecdote illustrates his character at the 1925 funeral of promoter Silvey Burns, where he single-handedly carried Burns’ heavy casket downstairs when pallbearers struggled. Wills was also a profound admirer of Dempsey, famously expressing regret for never having faced him, while also acknowledging Dempsey’s greatness. In an ideal world, Wills would be recognized for his distinguished career separate from Dempsey, highlighting the challenges faced by Black boxers in a prejudiced era.